Providing information on bulk materials handling (liquid and solid), plant systems engineering, specialty machine design, and process control engineering. Industry focus for the following posts are bulk handling systems, E-Liquid (E-Juice) manufacturing equipment, Biomass, plastics and polymers. For more information, visit PS&D or call (410) 861-6437

Saturday, July 22, 2017

Process Systems and Design: A Little Shameless Self Promotion

A little video promoting our plant engineering and design services .. thanks for indulging us!

Wednesday, July 12, 2017

The Ethanol Production Process

|

| Ethanol Plant |

Dry-milling plants have higher yields of ethanol. The wet mill is more versatile, though, because the starch stream, being nearly pure, can be converted into other products (for instance, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS)). Co-product output from the wet mill is also more valuable.

In each process, the corn is cleaned before it enters the mill. In the dry mill, the milling step consists of grinding the corn and adding water to form the mash. In the wet mill, milling and processing are more elaborate because the grain must be separated into its components. First, the corn is steeped in a solution of water and sulfur dioxide (SO2) to loosen the germ and hull fiber. This 30- to 40-hour extra soaking step requires additional tanks that contribute to the higher construction costs. Then the germ is removed from the kernel, and corn oil is extracted from the germ. The remaining germ meal is added to the hulls and fiber to form the corn gluten feed (CGF) stream. Gluten, a high-protein portion of the kernel, is also separated and becomes corn gluten meal (CGM), a high-value, high-protein (60 percent) animal feed. The corn oil, CGF, CGM, and other products that result from the production of ethanol are termed co-products.

Unlike in dry milling, where the entire mash is fermented, in wet milling only the starch is fermented. The starch is then cooked, or liquefied, and an enzyme added to hydrolyze, or segment, the long starch chains. In dry milling, the mash, which still contains all the feed co-products, is cooked and an enzyme added. In both systems a second enzyme is added to turn the starch into a simple sugar, glucose, in a process called saccharification. Saccharification in a wet mill may take up to 48 hours, though it usually requires less time, depending on the amount of enzyme used. In modern dry mills, saccharification has been combined with the fermentation step in a process called simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF).

Glucose is then fermented into ethanol by yeast (the SSF step in most dry- milling facilities). The mash must be cooled to at least 95deg. F before the yeast is added. The yeast converts the glucose into ethanol, carbon dioxide (CO2), and small quantities of other organic compounds during the fermentation process. The yeast, which produces almost as much CO2 as ethanol, ceases fermenting when the concentration of alcohol is between 12 and 18 percent by volume, with the average being about 15 percent. An energy-consuming process, the distillation step, is required to separate the ethanol from the alcohol-water solution. This two-part step consists of primary distillation and dehydration. Primary distillation yields ethanol that is up to 95-percent free of water. Dehydration brings the concentration of ethanol up to 99 percent. Finally, gasoline is added to the ethanol in a step called “denaturing,” making it unfit for human consumption when it leaves the plant.

The co-products from wet milling are corn oil and the animal feeds corn gluten feed (CGF) and corn gluten meal (CGM). Dry milling production leaves, in addition to ethanol, distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS). The feed co-products must be concentrated in large evaporators and then dried. The CO2 may or may not be captured and sold.

Reprinted from USDA publication “New Technologies in Ethanol Production”

Friday, June 30, 2017

Happy Fourth of July from PSD

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness."

THOMAS JEFFERSON, Declaration of Independence

THOMAS JEFFERSON, Declaration of Independence

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Dust Collection Systems in Mineral Processing Plants

Dust collection systems are the most widely used engineering control technique employed by mineral processing plants to control dust and lower workers' respirable dust exposure. A well- integrated dust collection system has multiple benefits, resulting in a dust-free environment that increases productivity and reclaims valuable product.

The most common dust control techniques at mineral processing plants utilize local exhaust ventilation systems (LEVs). These systems capture dust generated by various processes such as crushing, milling, screening, drying, bagging, and loading, and then transport this dust via ductwork to a dust collection filtering device. By capturing the dust at the source, it is prevented from becoming liberated into the processing plant and contaminating the breathing atmosphere of the workers.

LEV systems use a negative pressure exhaust ventilation technique to capture the dust before it escapes from the processing operation. Effective systems typically incorporate a capture device (enclosure, hood, chute, etc.) designed to maximize the collection potential.

As part of a dust collection system, LEVs possess a number of advantages:

In most cases, dust is generated in obvious ways. Anytime an operation is transporting, refining, or processing a dry material, there is a great likelihood that dust will be generated. It also follows that once the dust is liberated into the plant environment, it produces a dust cloud that may threaten worker health. In addition, high dust levels can impede visibility and thus directly affect the safety of workers.

The five areas that typically produce dust that must be controlled are as follows:

Dust control systems involve multiple engineering decisions, including the efficient use of available space, the length of duct runs, the ease of returning collected dust to the process, the necessary electrical requirements, and the selection of optimal filter and control equipment. Further, key decisions must be made about whether a centralized system or multiple systems are best for the circumstances. Critical engineering decisions involve defining the problem, selecting the best equipment for each job, and designing the best dust collection system for the particular needs of an operation.

For more information on dust control systems, contact Process Systems Design by visiting http://processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

The most common dust control techniques at mineral processing plants utilize local exhaust ventilation systems (LEVs). These systems capture dust generated by various processes such as crushing, milling, screening, drying, bagging, and loading, and then transport this dust via ductwork to a dust collection filtering device. By capturing the dust at the source, it is prevented from becoming liberated into the processing plant and contaminating the breathing atmosphere of the workers.

LEV systems use a negative pressure exhaust ventilation technique to capture the dust before it escapes from the processing operation. Effective systems typically incorporate a capture device (enclosure, hood, chute, etc.) designed to maximize the collection potential.

As part of a dust collection system, LEVs possess a number of advantages:

- the ability to capture and eliminate very fine particles that are difficult to control using wet suppression techniques;

- the option of reintroducing the material captured back into the production process or discarding the material so that it is not a detriment later in the process; and

- consistent performance in cold weather conditions because of not being greatly impacted by low temperatures, as are wet suppression systems.

In most cases, dust is generated in obvious ways. Anytime an operation is transporting, refining, or processing a dry material, there is a great likelihood that dust will be generated. It also follows that once the dust is liberated into the plant environment, it produces a dust cloud that may threaten worker health. In addition, high dust levels can impede visibility and thus directly affect the safety of workers.

The five areas that typically produce dust that must be controlled are as follows:

- The transfer points of conveying systems, where material falls while being transferred to another piece of equipment. Examples include the discharge of one belt conveyor to another belt conveyor, storage bin, or bucket elevator.

- Specific processes such as crushing, drying, screening, mixing, blending, bag unloading, and truck or railcar loading.

- Operations involving the displacement of air such as bag filling, palletizing, or pneumatic filling of silos.

- Outdoor areas where potential dust sources are uncontrolled, such as core and blast hole drilling.

- Outdoor areas such as haul roads, stockpiles, and miscellaneous unpaved areas where potential dust-generating material is disturbed by various mining-related activities and high-wind events.

Dust control systems involve multiple engineering decisions, including the efficient use of available space, the length of duct runs, the ease of returning collected dust to the process, the necessary electrical requirements, and the selection of optimal filter and control equipment. Further, key decisions must be made about whether a centralized system or multiple systems are best for the circumstances. Critical engineering decisions involve defining the problem, selecting the best equipment for each job, and designing the best dust collection system for the particular needs of an operation.

For more information on dust control systems, contact Process Systems Design by visiting http://processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Equipment Used in Crushed Stone Processing

Major rock types processed by the crushed stone industry include limestone, granite, dolomite, traprock, sandstone, quartz, and quartzite. Minor types include calcareous marl, marble, shell, and slate. Major mineral types processed by the pulverized minerals industry, a subset of the crushed stone processing industry, include calcium carbonate, talc, and barite. Industry classifications vary considerably and, in many cases, do not reflect actual geological definitions.

Rock and crushed stone products generally are loosened by drilling and blasting and then are loaded by power shovel or front-end loader into large haul trucks that transport the material to the processing operations. Techniques used for extraction vary with the nature and location of the deposit. Processing operations may include crushing, screening, size classification, material handling and storage operations. All of these processes can be significant sources of PM and PM-10 emissions if uncontrolled.

Quarried stone normally is delivered to the processing plant by truck and is dumped into a bin. A feeder or screens separate large boulders from finer rocks that do not require primary crushing, thus reducing the load to the primary crusher. Jaw, impactor, or gyratory crushers are usually used for initial reduction. The crusher product, normally 7.5 to 30 centimeters (3 to 12 inches) in diameter, and the grizzly throughs (undersize material) are discharged onto a belt conveyor and usually are conveyed to a surge pile for temporary storage or are sold as coarse aggregates.

The stone from the surge pile is conveyed to a vibrating inclined screen called the scalping screen. This unit separates oversized rock from the smaller stone. The undersized material from the scalping screen is considered to be a product stream and is transported to a storage pile and sold as base material. The stone that is too large to pass through the top deck of the scalping screen is processed in the secondary crusher. Cone crushers are commonly used for secondary crushing (although impact crushers are sometimes used), which typically reduces material to about 2.5 to 10 centimeters (1 to 4 inches). The material (throughs) from the second level of the screen bypasses the secondary crusher because it is sufficiently small for the last crushing step. The output from the secondary crusher and the throughs from the secondary screen are transported by conveyor to the tertiary circuit, which includes a sizing screen and a tertiary crusher.

Tertiary crushing is usually performed using cone crushers or other types of impactor crushers. Oversize material from the top deck of the sizing screen is fed to the tertiary crusher. The tertiary crusher output, which is typically about 0.50 to 2.5 centimeters (3/16th to 1 inch), is returned to the sizing screen. Various product streams with different size gradations are separated in the screening operation. The products are conveyed or trucked directly to finished product bins, to open area stock piles, or to other processing systems such as washing, air separators, and screens and classifiers (for the production of manufactured sand).

Some stone crushing plants produce manufactured sand. This is a small-sized rock product with a maximum size of 0.50 centimeters (3/16th inch). Crushed stone from the tertiary sizing screen is sized in a vibrating inclined screen (fines screen) with relatively small mesh sizes.

Oversized material is processed in a cone crusher or a hammermill (fines crusher) adjusted to produce small diameter material. The output is returned to the fines screen for resizing.

In certain cases, stone washing is required to meet particulate end product specifications or demands.

For more information on equipment designed for processing crushed stone, visit Process Systems Design at http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Rock and crushed stone products generally are loosened by drilling and blasting and then are loaded by power shovel or front-end loader into large haul trucks that transport the material to the processing operations. Techniques used for extraction vary with the nature and location of the deposit. Processing operations may include crushing, screening, size classification, material handling and storage operations. All of these processes can be significant sources of PM and PM-10 emissions if uncontrolled.

Quarried stone normally is delivered to the processing plant by truck and is dumped into a bin. A feeder or screens separate large boulders from finer rocks that do not require primary crushing, thus reducing the load to the primary crusher. Jaw, impactor, or gyratory crushers are usually used for initial reduction. The crusher product, normally 7.5 to 30 centimeters (3 to 12 inches) in diameter, and the grizzly throughs (undersize material) are discharged onto a belt conveyor and usually are conveyed to a surge pile for temporary storage or are sold as coarse aggregates.

The stone from the surge pile is conveyed to a vibrating inclined screen called the scalping screen. This unit separates oversized rock from the smaller stone. The undersized material from the scalping screen is considered to be a product stream and is transported to a storage pile and sold as base material. The stone that is too large to pass through the top deck of the scalping screen is processed in the secondary crusher. Cone crushers are commonly used for secondary crushing (although impact crushers are sometimes used), which typically reduces material to about 2.5 to 10 centimeters (1 to 4 inches). The material (throughs) from the second level of the screen bypasses the secondary crusher because it is sufficiently small for the last crushing step. The output from the secondary crusher and the throughs from the secondary screen are transported by conveyor to the tertiary circuit, which includes a sizing screen and a tertiary crusher.

Tertiary crushing is usually performed using cone crushers or other types of impactor crushers. Oversize material from the top deck of the sizing screen is fed to the tertiary crusher. The tertiary crusher output, which is typically about 0.50 to 2.5 centimeters (3/16th to 1 inch), is returned to the sizing screen. Various product streams with different size gradations are separated in the screening operation. The products are conveyed or trucked directly to finished product bins, to open area stock piles, or to other processing systems such as washing, air separators, and screens and classifiers (for the production of manufactured sand).

Some stone crushing plants produce manufactured sand. This is a small-sized rock product with a maximum size of 0.50 centimeters (3/16th inch). Crushed stone from the tertiary sizing screen is sized in a vibrating inclined screen (fines screen) with relatively small mesh sizes.

Oversized material is processed in a cone crusher or a hammermill (fines crusher) adjusted to produce small diameter material. The output is returned to the fines screen for resizing.

In certain cases, stone washing is required to meet particulate end product specifications or demands.

For more information on equipment designed for processing crushed stone, visit Process Systems Design at http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Thursday, June 8, 2017

Dilute Phase Pneumatic Conveying

|

| Dilute Phase Pneumatic Conveying |

Considering designing a pneumatic conveying system yourself? Probably not a good idea. There's as much art involved as there is science and such a design should be left to professionals. Consider that even different grades of the same material have been known to convey differently. Testing is a must (as you'll see from the method below). Before you can even make any good judgements from the method presented here, you need to know solid friction factor for your solids (which we'll discuss later) and the minimum gas velocity required to move your particles. So, if you're involved in designing a system from the ground up, seek assistance from reputable people in the field of conveying. If you're already familiar with your solids, the method below can be used to examine the pressure loss expected in your system. The method presented here is very good and has been stood the test of real systems over time.

Read the full white paper (courtesy of Process Systems & Design) below:

Thursday, June 1, 2017

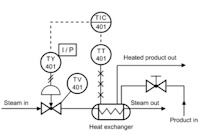

Piping & Instrumentation Diagram in Process Control

P&ID's (piping & instrumentation diagrams), or Process and Control Flow Diagrams, are schematic representations of a process control system and used to illustrate the piping system, process flow, installed equipment, and process instrumentation and functional relationships therein.

Intended to provide a “picture” of all of piping including the physical branches, valves, equipment, instrumentation and interlocks. The P&ID uses a set of standard symbols representing each component of the system such as instruments, piping, motors, pumps, etc.

P&ID’s can be very detailed and are generally the primary source from where instrument and equipment lists are generated and are very handy reference for maintenance and upgrades. P&ID’s also play an important early role in safety planning through a better understanding of the operability and relationships of all components in the system.

For more information on any process system design or process engineering requirement, visit http://www.processsytemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Intended to provide a “picture” of all of piping including the physical branches, valves, equipment, instrumentation and interlocks. The P&ID uses a set of standard symbols representing each component of the system such as instruments, piping, motors, pumps, etc.

P&ID’s can be very detailed and are generally the primary source from where instrument and equipment lists are generated and are very handy reference for maintenance and upgrades. P&ID’s also play an important early role in safety planning through a better understanding of the operability and relationships of all components in the system.

For more information on any process system design or process engineering requirement, visit http://www.processsytemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)