"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness."

THOMAS JEFFERSON, Declaration of Independence

Providing information on bulk materials handling (liquid and solid), plant systems engineering, specialty machine design, and process control engineering. Industry focus for the following posts are bulk handling systems, E-Liquid (E-Juice) manufacturing equipment, Biomass, plastics and polymers. For more information, visit PS&D or call (410) 861-6437

Friday, June 30, 2017

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Dust Collection Systems in Mineral Processing Plants

Dust collection systems are the most widely used engineering control technique employed by mineral processing plants to control dust and lower workers' respirable dust exposure. A well- integrated dust collection system has multiple benefits, resulting in a dust-free environment that increases productivity and reclaims valuable product.

The most common dust control techniques at mineral processing plants utilize local exhaust ventilation systems (LEVs). These systems capture dust generated by various processes such as crushing, milling, screening, drying, bagging, and loading, and then transport this dust via ductwork to a dust collection filtering device. By capturing the dust at the source, it is prevented from becoming liberated into the processing plant and contaminating the breathing atmosphere of the workers.

LEV systems use a negative pressure exhaust ventilation technique to capture the dust before it escapes from the processing operation. Effective systems typically incorporate a capture device (enclosure, hood, chute, etc.) designed to maximize the collection potential.

As part of a dust collection system, LEVs possess a number of advantages:

In most cases, dust is generated in obvious ways. Anytime an operation is transporting, refining, or processing a dry material, there is a great likelihood that dust will be generated. It also follows that once the dust is liberated into the plant environment, it produces a dust cloud that may threaten worker health. In addition, high dust levels can impede visibility and thus directly affect the safety of workers.

The five areas that typically produce dust that must be controlled are as follows:

Dust control systems involve multiple engineering decisions, including the efficient use of available space, the length of duct runs, the ease of returning collected dust to the process, the necessary electrical requirements, and the selection of optimal filter and control equipment. Further, key decisions must be made about whether a centralized system or multiple systems are best for the circumstances. Critical engineering decisions involve defining the problem, selecting the best equipment for each job, and designing the best dust collection system for the particular needs of an operation.

For more information on dust control systems, contact Process Systems Design by visiting http://processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

The most common dust control techniques at mineral processing plants utilize local exhaust ventilation systems (LEVs). These systems capture dust generated by various processes such as crushing, milling, screening, drying, bagging, and loading, and then transport this dust via ductwork to a dust collection filtering device. By capturing the dust at the source, it is prevented from becoming liberated into the processing plant and contaminating the breathing atmosphere of the workers.

LEV systems use a negative pressure exhaust ventilation technique to capture the dust before it escapes from the processing operation. Effective systems typically incorporate a capture device (enclosure, hood, chute, etc.) designed to maximize the collection potential.

As part of a dust collection system, LEVs possess a number of advantages:

- the ability to capture and eliminate very fine particles that are difficult to control using wet suppression techniques;

- the option of reintroducing the material captured back into the production process or discarding the material so that it is not a detriment later in the process; and

- consistent performance in cold weather conditions because of not being greatly impacted by low temperatures, as are wet suppression systems.

In most cases, dust is generated in obvious ways. Anytime an operation is transporting, refining, or processing a dry material, there is a great likelihood that dust will be generated. It also follows that once the dust is liberated into the plant environment, it produces a dust cloud that may threaten worker health. In addition, high dust levels can impede visibility and thus directly affect the safety of workers.

The five areas that typically produce dust that must be controlled are as follows:

- The transfer points of conveying systems, where material falls while being transferred to another piece of equipment. Examples include the discharge of one belt conveyor to another belt conveyor, storage bin, or bucket elevator.

- Specific processes such as crushing, drying, screening, mixing, blending, bag unloading, and truck or railcar loading.

- Operations involving the displacement of air such as bag filling, palletizing, or pneumatic filling of silos.

- Outdoor areas where potential dust sources are uncontrolled, such as core and blast hole drilling.

- Outdoor areas such as haul roads, stockpiles, and miscellaneous unpaved areas where potential dust-generating material is disturbed by various mining-related activities and high-wind events.

Dust control systems involve multiple engineering decisions, including the efficient use of available space, the length of duct runs, the ease of returning collected dust to the process, the necessary electrical requirements, and the selection of optimal filter and control equipment. Further, key decisions must be made about whether a centralized system or multiple systems are best for the circumstances. Critical engineering decisions involve defining the problem, selecting the best equipment for each job, and designing the best dust collection system for the particular needs of an operation.

For more information on dust control systems, contact Process Systems Design by visiting http://processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Equipment Used in Crushed Stone Processing

Major rock types processed by the crushed stone industry include limestone, granite, dolomite, traprock, sandstone, quartz, and quartzite. Minor types include calcareous marl, marble, shell, and slate. Major mineral types processed by the pulverized minerals industry, a subset of the crushed stone processing industry, include calcium carbonate, talc, and barite. Industry classifications vary considerably and, in many cases, do not reflect actual geological definitions.

Rock and crushed stone products generally are loosened by drilling and blasting and then are loaded by power shovel or front-end loader into large haul trucks that transport the material to the processing operations. Techniques used for extraction vary with the nature and location of the deposit. Processing operations may include crushing, screening, size classification, material handling and storage operations. All of these processes can be significant sources of PM and PM-10 emissions if uncontrolled.

Quarried stone normally is delivered to the processing plant by truck and is dumped into a bin. A feeder or screens separate large boulders from finer rocks that do not require primary crushing, thus reducing the load to the primary crusher. Jaw, impactor, or gyratory crushers are usually used for initial reduction. The crusher product, normally 7.5 to 30 centimeters (3 to 12 inches) in diameter, and the grizzly throughs (undersize material) are discharged onto a belt conveyor and usually are conveyed to a surge pile for temporary storage or are sold as coarse aggregates.

The stone from the surge pile is conveyed to a vibrating inclined screen called the scalping screen. This unit separates oversized rock from the smaller stone. The undersized material from the scalping screen is considered to be a product stream and is transported to a storage pile and sold as base material. The stone that is too large to pass through the top deck of the scalping screen is processed in the secondary crusher. Cone crushers are commonly used for secondary crushing (although impact crushers are sometimes used), which typically reduces material to about 2.5 to 10 centimeters (1 to 4 inches). The material (throughs) from the second level of the screen bypasses the secondary crusher because it is sufficiently small for the last crushing step. The output from the secondary crusher and the throughs from the secondary screen are transported by conveyor to the tertiary circuit, which includes a sizing screen and a tertiary crusher.

Tertiary crushing is usually performed using cone crushers or other types of impactor crushers. Oversize material from the top deck of the sizing screen is fed to the tertiary crusher. The tertiary crusher output, which is typically about 0.50 to 2.5 centimeters (3/16th to 1 inch), is returned to the sizing screen. Various product streams with different size gradations are separated in the screening operation. The products are conveyed or trucked directly to finished product bins, to open area stock piles, or to other processing systems such as washing, air separators, and screens and classifiers (for the production of manufactured sand).

Some stone crushing plants produce manufactured sand. This is a small-sized rock product with a maximum size of 0.50 centimeters (3/16th inch). Crushed stone from the tertiary sizing screen is sized in a vibrating inclined screen (fines screen) with relatively small mesh sizes.

Oversized material is processed in a cone crusher or a hammermill (fines crusher) adjusted to produce small diameter material. The output is returned to the fines screen for resizing.

In certain cases, stone washing is required to meet particulate end product specifications or demands.

For more information on equipment designed for processing crushed stone, visit Process Systems Design at http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Rock and crushed stone products generally are loosened by drilling and blasting and then are loaded by power shovel or front-end loader into large haul trucks that transport the material to the processing operations. Techniques used for extraction vary with the nature and location of the deposit. Processing operations may include crushing, screening, size classification, material handling and storage operations. All of these processes can be significant sources of PM and PM-10 emissions if uncontrolled.

Quarried stone normally is delivered to the processing plant by truck and is dumped into a bin. A feeder or screens separate large boulders from finer rocks that do not require primary crushing, thus reducing the load to the primary crusher. Jaw, impactor, or gyratory crushers are usually used for initial reduction. The crusher product, normally 7.5 to 30 centimeters (3 to 12 inches) in diameter, and the grizzly throughs (undersize material) are discharged onto a belt conveyor and usually are conveyed to a surge pile for temporary storage or are sold as coarse aggregates.

The stone from the surge pile is conveyed to a vibrating inclined screen called the scalping screen. This unit separates oversized rock from the smaller stone. The undersized material from the scalping screen is considered to be a product stream and is transported to a storage pile and sold as base material. The stone that is too large to pass through the top deck of the scalping screen is processed in the secondary crusher. Cone crushers are commonly used for secondary crushing (although impact crushers are sometimes used), which typically reduces material to about 2.5 to 10 centimeters (1 to 4 inches). The material (throughs) from the second level of the screen bypasses the secondary crusher because it is sufficiently small for the last crushing step. The output from the secondary crusher and the throughs from the secondary screen are transported by conveyor to the tertiary circuit, which includes a sizing screen and a tertiary crusher.

Tertiary crushing is usually performed using cone crushers or other types of impactor crushers. Oversize material from the top deck of the sizing screen is fed to the tertiary crusher. The tertiary crusher output, which is typically about 0.50 to 2.5 centimeters (3/16th to 1 inch), is returned to the sizing screen. Various product streams with different size gradations are separated in the screening operation. The products are conveyed or trucked directly to finished product bins, to open area stock piles, or to other processing systems such as washing, air separators, and screens and classifiers (for the production of manufactured sand).

Some stone crushing plants produce manufactured sand. This is a small-sized rock product with a maximum size of 0.50 centimeters (3/16th inch). Crushed stone from the tertiary sizing screen is sized in a vibrating inclined screen (fines screen) with relatively small mesh sizes.

Oversized material is processed in a cone crusher or a hammermill (fines crusher) adjusted to produce small diameter material. The output is returned to the fines screen for resizing.

In certain cases, stone washing is required to meet particulate end product specifications or demands.

For more information on equipment designed for processing crushed stone, visit Process Systems Design at http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Thursday, June 8, 2017

Dilute Phase Pneumatic Conveying

|

| Dilute Phase Pneumatic Conveying |

Considering designing a pneumatic conveying system yourself? Probably not a good idea. There's as much art involved as there is science and such a design should be left to professionals. Consider that even different grades of the same material have been known to convey differently. Testing is a must (as you'll see from the method below). Before you can even make any good judgements from the method presented here, you need to know solid friction factor for your solids (which we'll discuss later) and the minimum gas velocity required to move your particles. So, if you're involved in designing a system from the ground up, seek assistance from reputable people in the field of conveying. If you're already familiar with your solids, the method below can be used to examine the pressure loss expected in your system. The method presented here is very good and has been stood the test of real systems over time.

Read the full white paper (courtesy of Process Systems & Design) below:

Thursday, June 1, 2017

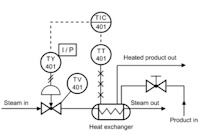

Piping & Instrumentation Diagram in Process Control

P&ID's (piping & instrumentation diagrams), or Process and Control Flow Diagrams, are schematic representations of a process control system and used to illustrate the piping system, process flow, installed equipment, and process instrumentation and functional relationships therein.

Intended to provide a “picture” of all of piping including the physical branches, valves, equipment, instrumentation and interlocks. The P&ID uses a set of standard symbols representing each component of the system such as instruments, piping, motors, pumps, etc.

P&ID’s can be very detailed and are generally the primary source from where instrument and equipment lists are generated and are very handy reference for maintenance and upgrades. P&ID’s also play an important early role in safety planning through a better understanding of the operability and relationships of all components in the system.

For more information on any process system design or process engineering requirement, visit http://www.processsytemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Intended to provide a “picture” of all of piping including the physical branches, valves, equipment, instrumentation and interlocks. The P&ID uses a set of standard symbols representing each component of the system such as instruments, piping, motors, pumps, etc.

P&ID’s can be very detailed and are generally the primary source from where instrument and equipment lists are generated and are very handy reference for maintenance and upgrades. P&ID’s also play an important early role in safety planning through a better understanding of the operability and relationships of all components in the system.

For more information on any process system design or process engineering requirement, visit http://www.processsytemsdesign.com or call (410) 861-6437.

Monday, May 22, 2017

Safety Video: Refinery Plant Explosion Animation

Brought to you as a courtesy of U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB.gov) and Process Systems and Design (http://www.processsystemsdesign.com).

Video reviews the circumstances that led up to a 2015 explosion at a refinery in Torrence CA.

Process Systems and Design is a team of technical and business experts across a spectrum of industries who specialize in all aspects of process control and material handling equipment design, construction, and support. They can be reached by visiting http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

Video reviews the circumstances that led up to a 2015 explosion at a refinery in Torrence CA.

Process Systems and Design is a team of technical and business experts across a spectrum of industries who specialize in all aspects of process control and material handling equipment design, construction, and support. They can be reached by visiting http://www.processsystemsdesign.com or calling (410) 861-6437.

Monday, May 8, 2017

Intellectual Property Related to Vaping, E Liquid & ENDS

|

| Vaping |

The FDA unwittingly intervened in the middle of the vaping industry’s technology development cycle and changed the rules of the game. As we all know, that has caused a firestorm of controversy and some industry paralysis around innovation. Investment in innovation requires clear business goals and the business environment is unclear until the new deeming regulations are fully imposed, repealed or scaled-back. Slick, visually appealing, flavorful and compact once drove the research and development cycle, now accuracy, repeatability, measurability and systems interaction will take precedence to comply with the new regulations if they stand as I believe they will.

Thus far, the vaping industry has been built largely on branding, a loyal customer base and trade secrets to create and protect the competitive advantage that exists in the various vape-related businesses. Most e-liquid formulations are kept secret although the manner in which the secrets are kept may not meet the legal hurdle of “due care”. In simple terms, due care requires that one goes through some extraordinary efforts not to expose the secret information to those who would disclose it or profit from it. Disclosure nullifies the trade secret and nothing can be done to put that horse back into the barn. Once a trade secret is in the public domain, it can’t be patented or made secret again. Beyond trade secrets, mostly around formulae, some patents have been filed against the various ENDS devices, cartomizers and power supply’s but they are few relative to the quantity of devices and their derivations on the market today. Very few patents have been filed against the systems or hardware that blend e-liquid either which suggests that there is either nothing novel about the equipment or the inventors intend to keep it a trade secret. Moreover, since demand outpaced supply historically, the need for unique competitive advantage was somewhat diminished, as I stated in a prior published paper*. Therefore, over the past decade all boats rose with the tide. Everyone profited from the bow-wave created by the surge in the vaping market and protection of intellectual property was not a requirement for near term success. Long-term, sustainable success is a different story. Long-term sustainable success is built on well-protected intellectual property (IP). It is estimated that around 80% of the total value of the S&P 500 index is attributable to intangible assets, i.e. intellectual property of all types.

The landscape has changed dramatically for all businesses related to the vaping industry however. The recent deeming regulations will surely to drive a course correction as they kick in through 2018. One thing seems certain, the FDA regulations are here to stay in some form. Whatever innovation(IP) did exist prior to August 2016 is likely to become partly obsolete or possibly wholly obsolete dependent on which segment of the business you are in. Why so? Because the methods, processes, hardware, materials and designs that were sufficient to meet the needs of an unregulated environment are not likely to be sufficient to meet the needs of the new regulated environment. It’s that simple. The standard has changed and there is now a higher science required to meet that standard. The new standard will be grounded in repeatability and other metrics that are tied more to science, data collection and reporting than marketing alone. Smart businesses will leverage the science in their marketing pitches and I can already see it emerging in recent advertisements. The vaping industry supply chain businesses that hope to remain viable going forward will need to answer the larger questions. Are the thermo-mechanical processes executed by the ENDS device to vaporize the liquid repeatable within an “acceptable” range? Can the ENDS apparatus and the liquid when combined produce repeatable results for the user? Are the various thermal, chemical and mechanical interactions well understood? Do the developers and manufacturers of those commodities know what those results are in terms of toxicology? The answers to those questions and others are the kernels of intellectual property(IP) that will emerge by necessity from the R&D required to create the solutions. That’s the jist of it. Those who can determine which IP to create and protect and how to protect it will yield the golden goose, i.e. long-term competitive advantage.

Most of the heavy-hitters in the tobacco industry have already begun to put IP stakes in the ground. One indication is that Altria, Reynolds American, Japan Tobacco Int’l and British American Tobacco have collectively filed for almost 900 patents over the past few years. More than half of those patent applications are related to vaping in some way. That’s just the IP that we can see in the public domain via published patent applications. There is much more in trade secrets, undisclosed processes and know-how behind that. There always is. Think of it as a fence-line. Patents are the fence-posts. The mesh that covers the posts and creates the barrier are made up of the intellectual property that you can’t see.

If you are a small to mid-sized business trying to make it in the new world order that the FDA regulations have yielded, you should be concerned but not dissuaded. Even large companies like Altria, etc. who have patents in the vaping area do not typically have a comprehensive IP strategy that is adequate. I lead the team that created the IP strategy approach for The Boeing Company in recent years and I can tell you that very few large companies do this well. Super high-technology companies like those found in IT, communications and the pharma industries are the best at creating and executing an IP strategy. That’s largely because they can afford to invest oodles of money in patenting and defending their IP around the world. The rest of us have to be much more efficient at identifying the IP that has real long-term value and then determining how we protect it. That’s where a comprehensive IP strategy can pay huge dividends for your company, no matter what size it is. Accessible subject matter expertise and the agility that comes with being smaller than Altria can be significant strengths in any strategic planning, especially in IP where the kernels of value need to be identified. Prescriptive IP strategy is beyond the scope of this paper and I have written volumes on it. It’s different for different industries and different business models within industries. However, anyone can begin to work through the tenants of creating an IP strategy which is where most businesses of all sizes miss the mark.

An effective IP strategy starts with a laser focus on business objectives. Your organization, no matter how small should have a business strategy that drives everything you do. Ask yourself, can you achieve your business objectives in terms of product line throughput, quality(FDA) cost and pricing that you need to be market competitive? Do you currently have the technology, processes and equipment that you need to achieve your business strategy? If not, how will you acquire the necessary missing elements? Will you create them internally through company funding or acquire them externally through in-licensing, supply-chain partnerships or acquisition be it just the IP or the whole company? Most importantly, do you know which technology, formulae, processes and equipment will yield the greatest competitive advantage going forward? Where are you in the supply-chain and how do you intend to monetize your position? This is the most critical aspect of any worthwhile strategic plan, knowing what’s important to your bottom line and prioritizing it. Once you know that, you can begin to invest in and protect your existing and emerging IP commensurate with its value. Patents, copyrights, trades secrets and trademarks are the typical tools that one would use to protect not only the most critical, but all the intellectual property that your company has ownership of, rights in or both. All IP has some value. It’s just a matter of prioritizing the IP according to its value contribution. This extends to teaming agreements and other contracts wherein the rights and ownership you convey or are conveyed to you are codified and agreed to. Any solid IP strategy is built around a business, technology, IP relationship that is well understood by a diverse subject matter expert team and then shared with rest of the organization. Small, agile organizations can be very good at this because there are less buy-ins required and less people to share the plan with. Some of this comes down to simply marking all of your documents correctly and that’s virtually free. It all starts with a solid business plan.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)